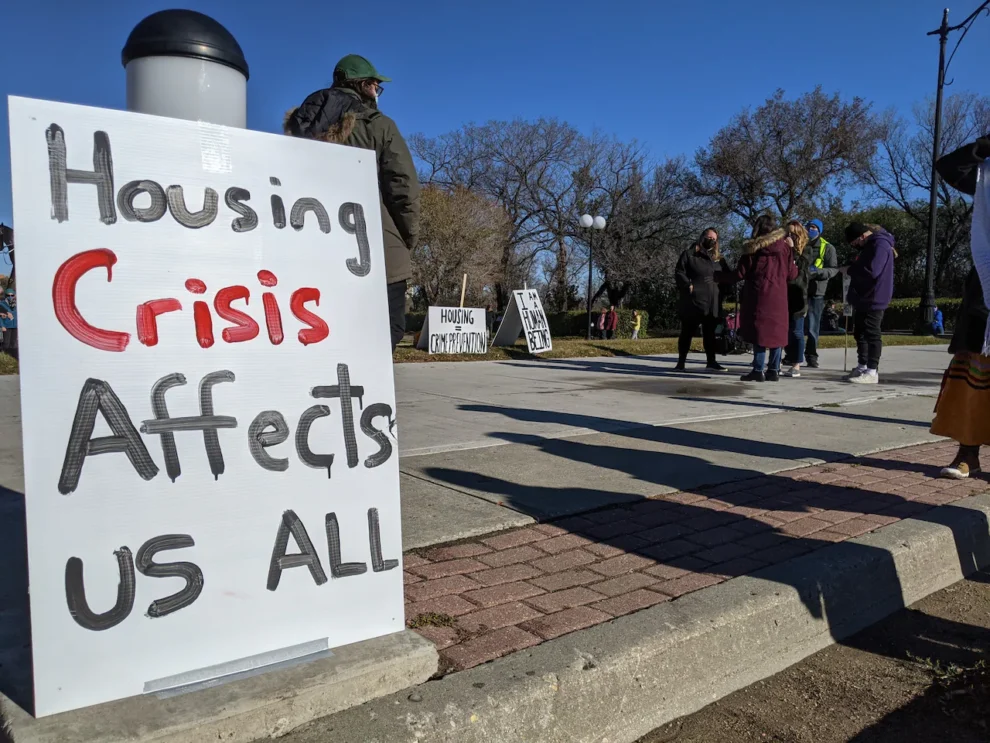

An employment lawyer says there has been a “huge rise” in Irish firms hiring abroad through third-party firms, who become the employer in the eyes of the authorities.

Ireland-based Tech firms are increasingly using ‘employer of record’ (EOR) companies in other countries to hire staff abroad, rather than moving them here due to the struggle of sourcing housing, an employment lawyer has said.

Linda Hynes, from Lewis Silkin Ireland, said that through using these third-party companies, which technically act as the worker’s legal employer, firms based here are able to contract staff who they can’t convince to relocate to Ireland.

She added that there has been a “huge rise” in this practice since the pandemic.

“Accommodation shortages and the cost of living here are some of the main factors at play. We have some clients where a huge amount of people that work for them are actually working remotely abroad, because they are just not able to convince them to relocate to Ireland,” Hynes explained.

Though employees are legally registered as being employed by these third-party firms, the work they do is actually for the end-user, which in this case is companies based in Ireland.

By paying for the services of these third-party companies, big tech firms based in Ireland can also avoid their profits being directly subject to corporation tax in different countries by being deemed to have set up offices in various locations because of employee numbers working there.

“It’s a way of trying to circumvent issues around tax, and social security. We have seen a whole industry grow up around flexible global working arrangements,” Hynes explained.

“This practice has a downside for Ireland, as these employees aren’t living here, or paying taxes and spending their money here,” she added.

EORs allow firms to essentially compare regulations in different countries when choosing where to set up a mini workforce abroad.

For example, Dublin-based EOR Boundless, which was founded in 2019, lists the different regulations in the countries it operates in including their minimum wage, mandatory benefits, employer tax, sick leave, maternity leave, and average amount of days off given.

Boundless informs employers that in Chile, the minimum monthly wage is 350,000 Chilean pesos, which is equivalent to just over €370. The minimum maternity leave is just over four months.

The Irish EOR explains to potential clients on its website that they simply have to select which country they want to employ in, fill out basic employee details, sign a third-party contract between Boundless, the employee and them, and it will “take care of the rest”, including payroll, taxes, payslips, and HR compliance.

Boundless says that it is always 100% complaint with employment laws in the countries it operates in. The Irish firm also states that there are some countries it won’t employ in, no matter how much demand there is, as it is not interested in “bending grey areas”.

A UK-based EOR, Bradford Jacobs, employs people in China, Saudi Arabia and Vietnam.

It tells employers that they should hire through an EOR because “governments are starting to enforce compliance laws that carry penalties for employee misclassification”.

Working overseas can lead to legal complications

Employment lawyer Hynes said that although many people dreamed of “working from the Bahamas” when remote working became widespread during the pandemic, the reality of life as a digital nomad working for a company based in Ireland can be complex.

While many big tech firms now have policies on “workcations”, some have found themselves having to work their way through legal complications after employees indefinitely relocated during the pandemic.

The general tipping point for tax residency is at the six months mark, meaning that an employee can inadvertently domicile by extending their stay abroad beyond 183 days within a 12-month period.

This can create income tax complications for both the employee and the employer, with the latter being at risk of being regarded as having established a permanent office in a second country, where it would be subject to corporation tax.

It can also have implications on the employees social security benefits.

Hynes is aware of roughly 15 cases where complications have arisen in this area for her clients over the last year.

“The most complicated cases arise when an employee is not honest with their employer about working from another country. It’s important that you keep your employer informed, and that you are in compliance with the secondary countries’ employment laws, because if not you could breach your contract, or see your ability to travel in the future limited,” she said.

Remote working

Hynes said that another area tech firms have been bringing in new policies in is remote working.

She said that while some companies she works with are trying to make hybrid working mandatory, due to low numbers of employees choosing to come into the office for part of the week, she doesn’t have any clients attempting to mandate a full return to the office.

The Work Life Balance and Miscellaneous Provisions Bill which is due to come into effect when the Dáil returns from recess is to be accompanied by a code of practice from the Workplace Relations Committee (WRC), which will guide employers on how to handle remote working requests.

“Under the new legislation, employees are going to have the right to request to work from home, but employers will also have the right to refuse them. My view is that the legislation is coming in too late, as most companies already have policies in place.

“What we could see happening is that employees raise internal grievances about having their request refused, and then resigning while arguing that they had no other option, and then claiming that it was a dismissal, and that the employer was in breach of contract.

“Another possibility is that some people, such a caregivers, could take cases against employers who refuse their requests by arguing that the decision 3as discriminatory,” Hynes said.

Source:The Journal