Europe has experienced a sudden and unprecedented increase in labour supply with the arrival of Ukrainian refugees from the Russia invasion. This column models the welfare and economic effects across EU countries. Real GDP increases in most countries, but especially in countries that are able to build more capital structures to accommodate the increased labour supply. Some countries that are not able to accumulate capital fast enough experience a decline in output. The impact varies across parts of the workforce – low-skilled labour, high-skilled labour, and owners of capital – and over time.

Understanding the economic effects of refugee immigration is a key question for economists and policymakers alike. Disentangling the short- and long-run response of the spatial distribution of economic activity to a large increase in labour supply requires taking into account not only the forward-looking aspect of costly migration decisions, but also the gradual accumulation of capital that may accompany – and drive – such decisions.

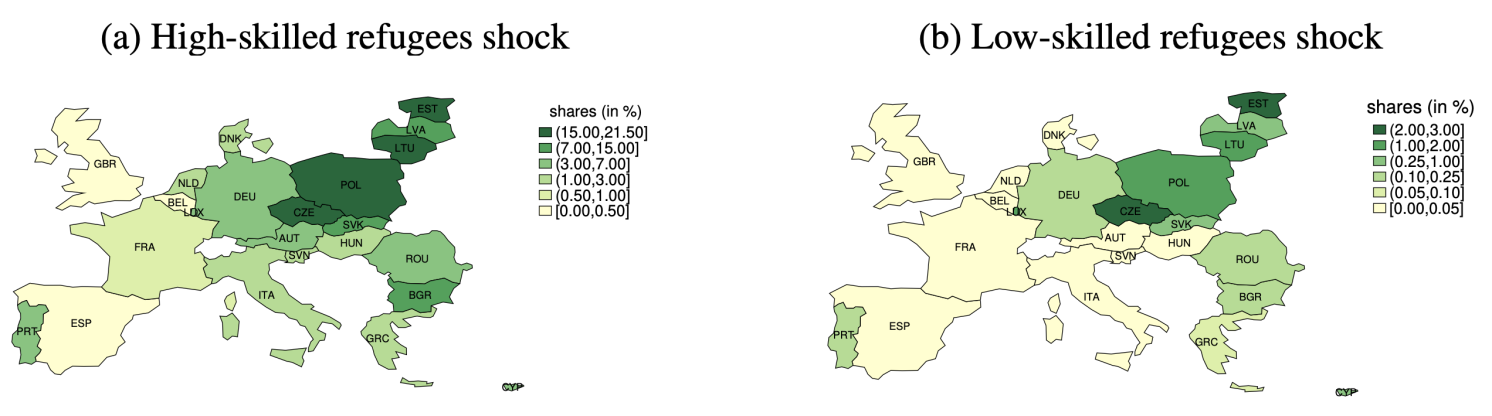

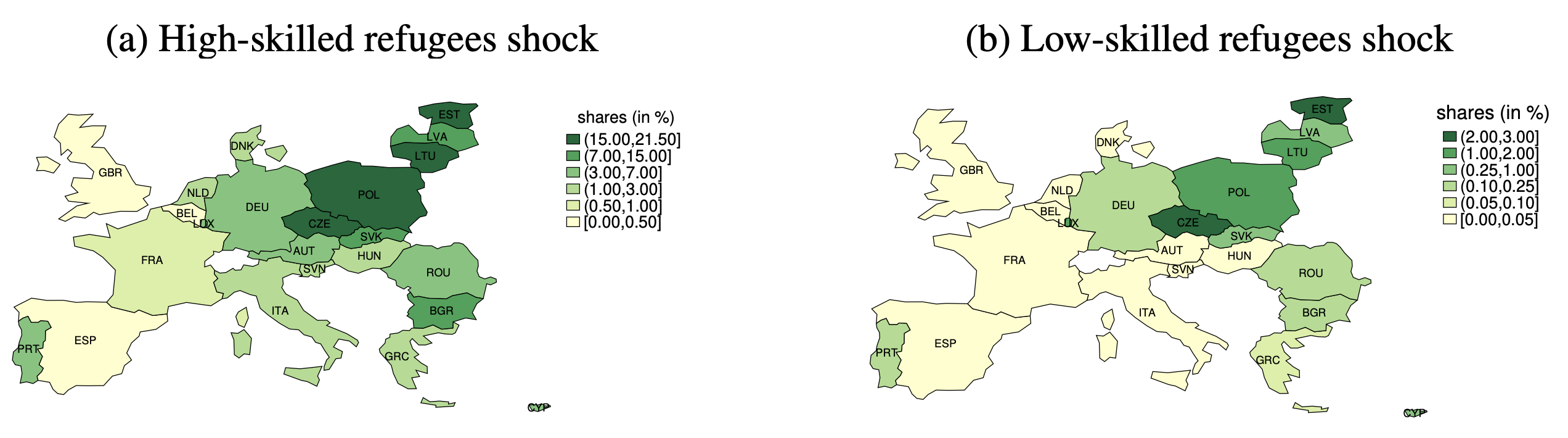

Today, the EU is facing the biggest refugee immigration crisis in its history. European countries have experienced a sudden and unprecedented increase in labour supply in the form of Ukrainian refugees from the 2022 Russia invasion. The numbers are striking: more than 8 million refugees, among which more than 4 million are of working age, geographically dispersed throughout Europe. Ukrainian refugees are mainly females and children, and a great majority of them have a higher education or college diploma. Figure 1 (from Caliendo et al. 2023) shows the number of refugees, by skill, as a share of the host country working age population. The distribution of refugees is highly heterogeneous across host countries – neighbouring countries receive the highest inflow of migrants – and they are generally high-skilled.

Based on this descriptive evidence, it is natural to wonder what the welfare and economic effects of the increase in labour supply across EU countries are, and if there is any possible migration policy that would make both refugee migrants and natives better off. Answering these questions requires adopting a structural approach informed by detailed data.

Figure 1 The labour supply shock due to Ukrainian refugees

Note: The figures present the number of refugees as a share of the host country working-age population, by skill level.

Source: Caliendo et al. (2023)

In a new paper (Caliendo et al. 2023) we develop a unifying framework – a dynamic general equilibrium model – that brings together migration (as in Caliendo et al. 2021) and capital accumulation (as in Kleinman et al., 2022) to study the impact of the inflow of refugees to the heterogeneous countries that form the EU. Production of goods requires high-skilled and low-skilled labour and capital structures, and countries trade goods subject to bilateral trade costs. Households, who might be employed or non-employed, make forward-looking migration decisions, and decide optimally where to locate each period subject to mobility frictions and idiosyncratic taste shocks. Immobile landowners (who we also refer as capitalists) have an investment technology to build capital structures (which they rent to local firms) in each country and decide the optimal stock of capital each period to maximise the present discounted value of their consumption.

In the short run, an increase in the supply of labour strains the use of capital structures that take time to build and impacts the return to capital and the price index, which affects the real return to accumulating capital across countries. Over time, countries that build capital structures can take advantage of the increase in labour supply and are able to increase output, resulting in potential long-run benefits.

A quantitative evaluation of the effects of the Ukrainian refugee migration shock requires information on the stock of Ukrainian refugees across each European country by education level, age, and employment status. We track the number of refugees from Ukraine in 23 European countries and the rest of the world using the second round of the survey of intentions and perspectives of refugees from Ukraine carried out by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR 2022). We focus on working-age refugees aged between 18 and 59 years, which accounts for about 4.2 million refugees. We also use data on labour market skills, employment status, and migration patterns from the 2018-19 European Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), production and trade data from the most recent World Input-Output Database, and information on capital structures from the IMF Investment and Capital Stock Dataset.

We bring the model to the data to study the impact of the Ukrainian refugees on production, international trade, and migration flows across 23 European countries, all of which are members of the EU. Our model also determines the impact on household consumption, which serves as a proxy for welfare. Moreover, we use the model to assess the impact that various levels of capital investment, as well as different levels of labour market integration and different refugee policies, would have on all the outcomes.

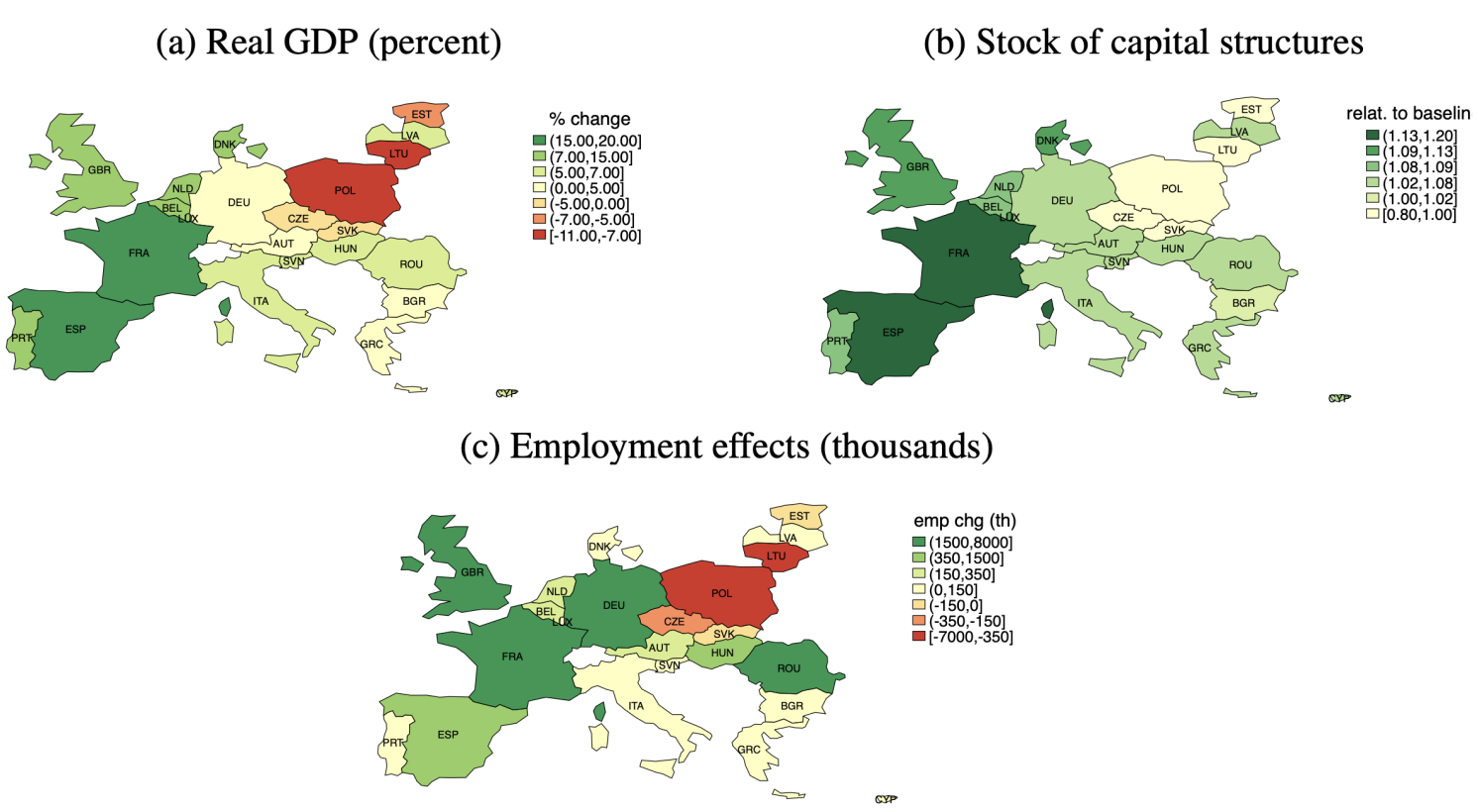

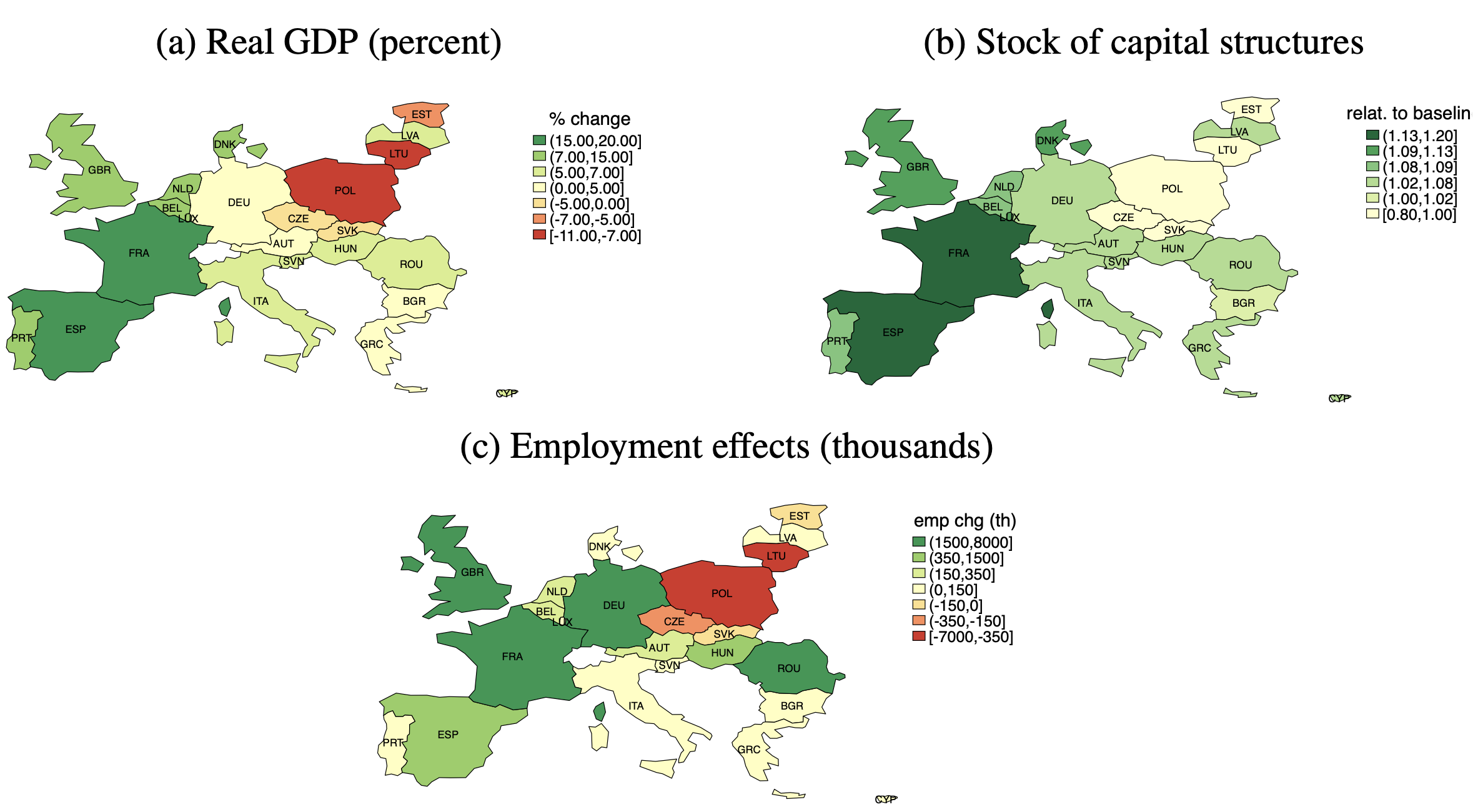

We find that the inflow of Ukrainian refugees increases aggregate real GDP in Europe by 3.6% in the long run. Real GDP increases in most countries, but especially in Western European countries that build more capital structures (Figure 2). Some Eastern European countries experience a decline in output as they are not able to accumulate capital fast enough to respond to the increase in labour supply. As a result, the inflow of refugees substantially strains capital structures in these countries in the short run, prompting households to move to countries where capital is growing faster, which has a negative impact on employment and incentives to build capital structures over time.

Figure 2 Aggregate effects (relative to baseline)

Note: the figures show the long-term (steady-state) aggregate effects of the labour supply shock across European countries relative to the baseline economy. Panel (a) presents The effects on real GDP, panel (b) shows the stock in captical structures in steady state relative to the baseline economy, and panel (b) presents the long-term effects on employment.

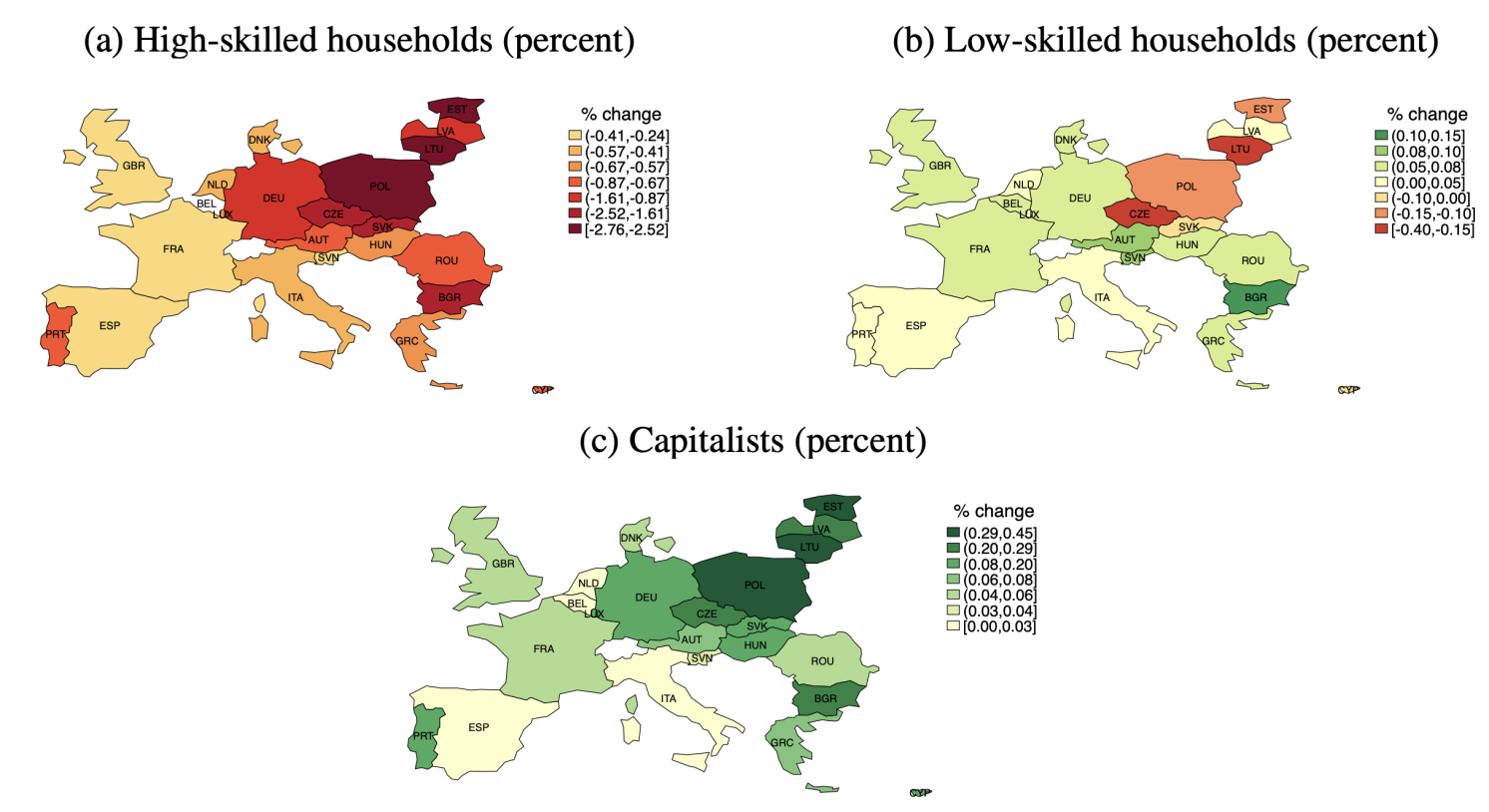

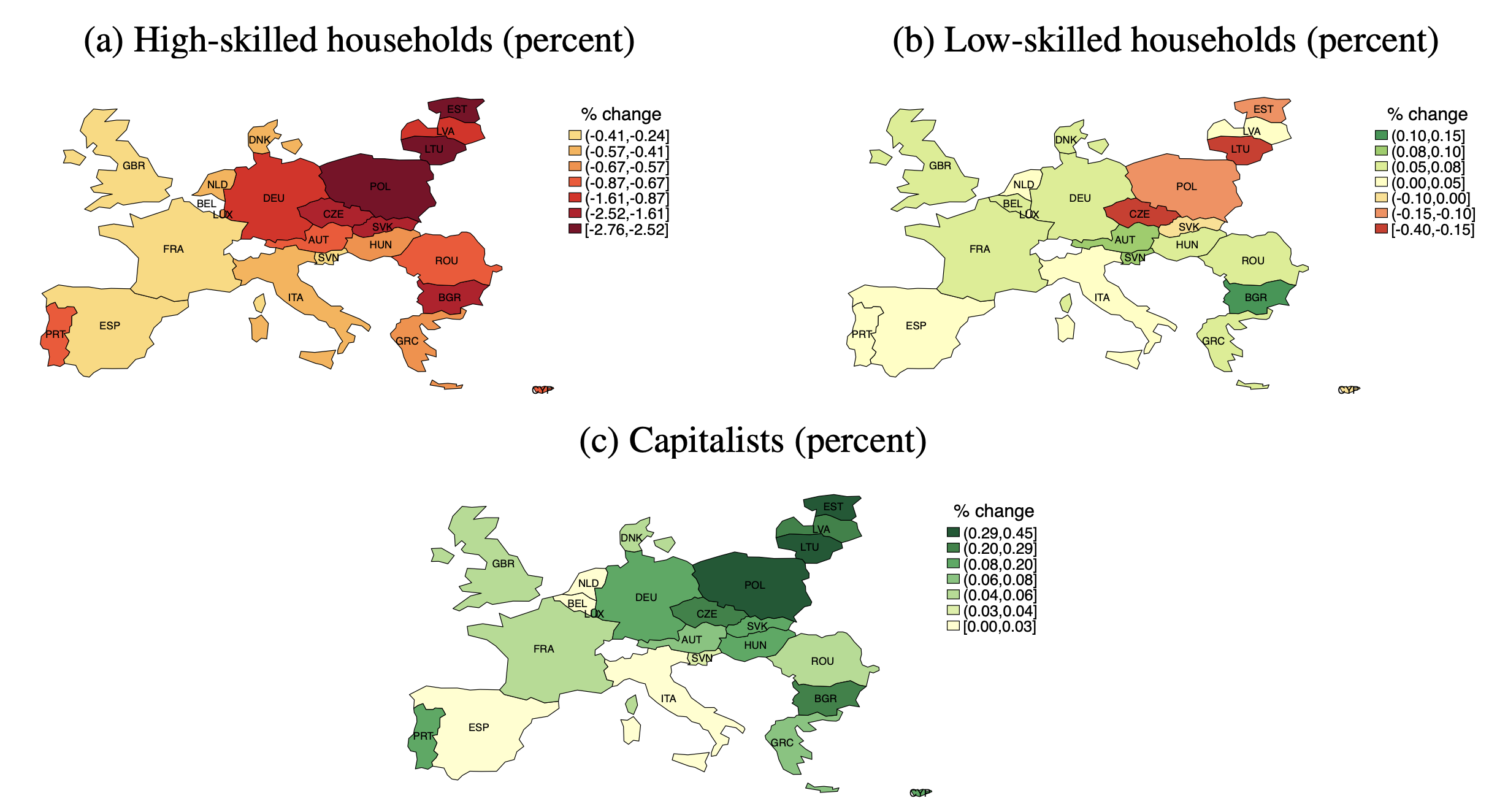

This result masks substantial heterogeneity, and the impact is different on different parts of the workforce – low-skilled labour, high-skilled labour, and owners of capital – and over time (Figure 3).

Low-skilled workers largely benefit in both the short and the long term. This is because most Ukrainian refugees are high-skilled workers and do not compete with low-skilled workers in the host countries. On the contrary, their skills and knowledge complement those of the low-skilled in the host countries, making them more productive.

High-skilled households are worse off in all countries as they face increased competition in the labour market from an increase in labor supply that is relatively high-skilled intensive, and the welfare losses are more pronounced in the countries that experienced a larger labour supply shock.

Importantly, since production also requires capital structures, the welfare gains for low-skilled households only materialises in countries that are able to build such structures. We also find distributional welfare effects between households and the owners of capital across countries. In particular, the inflow of Ukrainian refugees increases the supply of labour and creates incentives to increase the demand for capital structures to scale up production across countries, which benefits capitalists.

Figure 3 Distributional welfare effects

Note: The figures show the welfare effects, measured at the change in consumption equivalent relative to the baseline economy, of the labour supply shock across European countries. Panel (a) presents the welfare effects for high-skilled householes, panel (b) shows the welfare effects for low-skilled households, and panel (c) presents the welfare effects for capitalists.

The welfare effects for households is highly correlated in the short run with the magnitude of the labour supply shock. The intuition comes from the fact that in the short run, capital structures are mostly a fixed factor; hence, the inflow of Ukrainian refugees congests capital structures and increases the price index. Over time, the ability of a country to accumulate capital structures contributes to accommodating the labour supply shock. Accordingly, we find that the welfare effect for households is positively correlated with the change in the stock of capital structures across countries. Importantly, the accumulation of capital structures allows countries to reduce the welfare losses of high-skilled households and, as mentioned earlier, allows the low-skilled households to benefit from the high-skilled intensive labour supply shock.

Our model allows us to think about real world policies and assess their potential benefits (or losses). First, we investigate what would be the effect of the refugees’ immigration in a world in which people cannot freely move across countries in the EU (i.e. no labour market integration). We find that when people are not allowed to migrate, the increase in real GDP and in the stock of capital structures would be more modest. Intuitively, when people are free to migrate, they relocate where capital grows faster, and this leads to a larger increase in output in those countries. Second, we study whether redistributing migrants proportionally across countries according to their population would be beneficial. We find that this policy would make welfare losses for high-skilled workers more equitable, and welfare gains for low-skilled workers would be substantial everywhere in Europe. This policy avoids too much congestion of capital structures and price increases in some countries, leading to more uniform incentives to build capital structures, and as result, more generalised welfare gains for low-skilled households across countries.

Source : CEPR